Hot Shards

November 30, 2025

Overview

Hot shards are those unlucky partitions that see a disproportionate amount of traffic or work. Even if you use a “good” random hash function, hot shards still appear in production systems for reasons that have nothing to do with the hash function itself.

This post focuses on solutions: how real-world systems (DynamoDB, Spanner, Cassandra, ScyllaDB, Redis Cluster, Elasticsearch, etc.) actually mitigate hot shards.

TL;DR

- Random / uniform hashing only fixes key distribution problems.

- Hot shards still appear due to workload skew, time-series traffic, global keys, query patterns, and physical node imbalance.

- Production systems lean on microshards, adaptive capacity, key-splitting, write-sharding, replica-aware routing, and CRDT-style counters to keep things stable.

Table of Contents

1. Recap: Why Hot Shards Exist Even With Random Hashing

Before talking about solutions, we need to be precise about what we’re solving.

A shard can be “hot” for several root causes:

-

Hot keys

- A few keys receive 1000× more traffic than others (celebrity users, popular config keys, global counters).

-

Temporal / time-series hotspots

- Recent data or monotonic IDs funnel all new writes into a small region.

-

Query skew & range scans

- Queries that repeatedly target the same narrow slice of the key space, or scan wide ranges on a subset of shards.

-

Physical resource imbalance

- One node has worse hardware, heavier compaction, worse cache locality, or is just “unlucky” with shard placement.

-

Global logical keys / coordination hotspots

- Global locks, global version numbers, global rate-limiter buckets, etc., centralize traffic on a single shard.

-

Storage engine hotspots

- LSM compaction, GC, or disk-level behavior cause a shard to be much more expensive to maintain than others.

Random hashing only addresses:

“Are keys evenly distributed across shards?”

It does not guarantee:

“Is work evenly distributed across shards?”

The rest of this post is about how to fix each root cause.

2. Design Principles: The “Anti–Hot-Shard” Mindset

The techniques differ, but the guiding principles are fairly consistent:

- Over-partition (many small shards, not a few large ones).

- Monitor traffic + CPU + storage per shard.

- Move or split work when it becomes skewed.

- Avoid single global choke points (keys, locks, counters).

- Push complexity to the edges (routers, read aggregators, materialized views) rather than the hottest shard.

You can think of the overall architecture as:

“Lots of tiny pieces that can be moved around, and enough observability to know what to move.”

We’ll now go cause-by-cause.

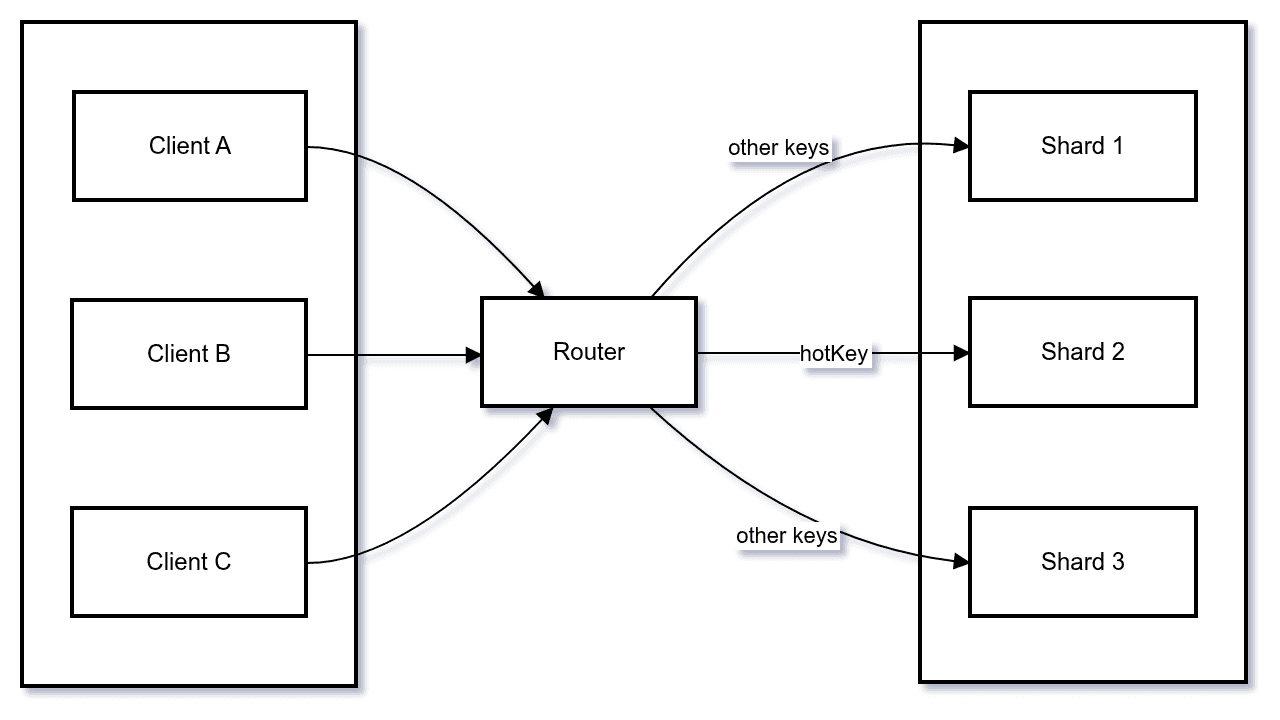

3. Hot Keys → Key-Level Load Splitting

3.1. Problem

A single key (or small set of keys) is much hotter than the rest:

- A celebrity’s user profile

- A single “global-progress” row

- A config document everyone reads

- A global counter or rate limiter bucket

Hashing doesn’t help: that one key maps to one shard.

3.2. Solution Pattern: “Key Salting” / “Key Splitting”

Instead of:

Key: user:12345You create logical shards of the same key:

user:12345#0

user:12345#1

user:12345#2

...Writes are spread across these “sub-keys”, and reads aggregate them.

3.3. Alternate Solution Pattern: Reverse Architecture of Writes and Reads

Twitter-style systems often avoid a hot shard on content poster by not using a single “global feed.” Instead, they either:

- Fan-out-on-write for normal keys: on tweet, push the tweet into each follower’s own timeline (sharded by follower ID), or

- Fan-out-on-read / hybrid for hot keys: for very high-follower accounts, don’t push to all followers at write time; instead, pull those tweets into a user’s home timeline dynamically when they fetch it. Tweet storage is sharded by tweet_id (high entropy), chunking follower lists, and caching tweet reads. Fan-out-on-read builds timelines from these sharded components — it doesn’t rely on key salting of the tweet itself.

3.4. Variants

| Pattern | How it works | Typical use cases | Tradeoffs & gotchas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random key suffixes (“salting”) | Append a random or round-robin suffix to a hot key, distribute subkeys across shards. | High-QPS writes to a single logical key (e.g., clickstream events for one page, chat messages for a busy room). | Readers must merge multiple subkeys; adds fan-out and aggregation latency. Harder to enforce strict ordering. |

| Sharded counters | Store multiple partial counters for the same logical counter; sum them on read or periodically. | Like counts, view counts, rate limits, metrics, quotas. | Approximate at read time unless you read all shards; more complicated to enforce exact 'less than or equal to N' invariants. |

| Adaptive key splitting | System detects a hot key and auto-creates more internal partitions for it. | Cloud databases and managed K/V stores (e.g., “adaptive capacity” features). | Black-box behavior; good for ops, but you lose precise control of layout; needs strong telemetry. |

3.5. When to use

- You see one customer, one tenant, or one resource dominating load.

- Per-key QPS is often more useful than per-shard QPS for triggering this.

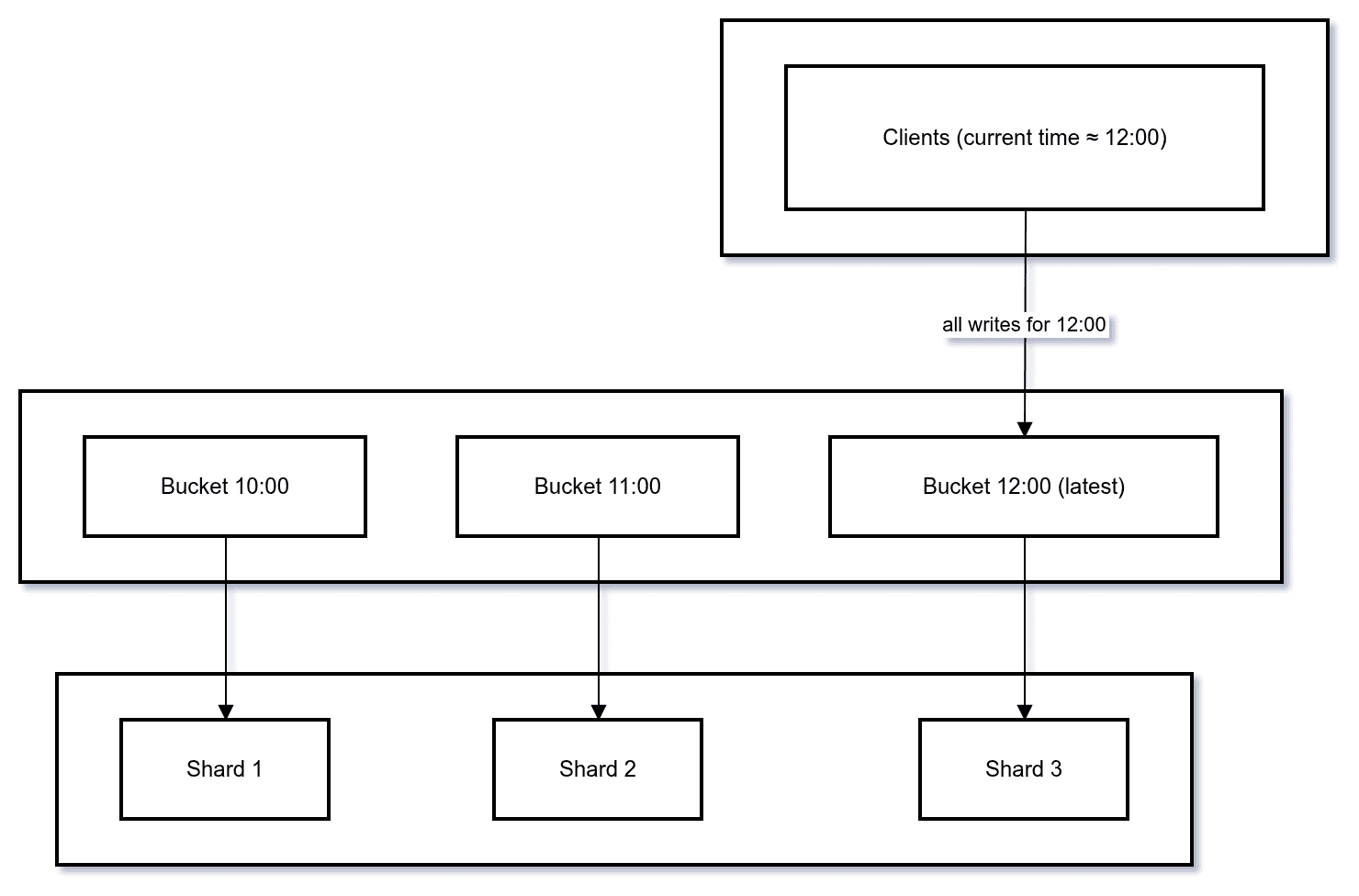

4. Temporal / Time-Series Hotspots → Write Sharding

4.1. Problem

Time-series workloads tend to pile writes onto the “latest” region:

- Monotonic IDs (Snowflake, UUIDv7)

- Time-bucketed keys (

events:2025-11-29-12:00) - Logs / metrics / traces

Even if the hash function is “good”, the newest buckets or IDs very often land on a small cluster of shards.

4.2. Solution Pattern: “Write Sharding” for Time Buckets

You keep the time locality at a coarse level (day/hour) but add randomness inside the bucket:

events:2025-11-29T12:00#0

events:2025-11-29T12:00#1

...

events:2025-11-29T12:00#31New writes for “now” are scattered across multiple sub-buckets. Reads that look at “12:00” will fan out across these 32 sub-buckets.

At 1:00PM, there would need to be a re-allocation of shards.

4.3. Variants

| Strategy | How it helps | Works best when... | Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized time-bucket keys | Scatter writes for one bucket across multiple partitions. | Readers naturally use fairly wide time ranges and can tolerate fan-out. | Readers must query multiple partitions per time slice; some extra network + CPU overhead. |

| Multiple “hot” partitions per topic | Instead of 1 partition per topic/tenant, you maintain N partitions in parallel. | Message queues (Kafka-like), streaming ingestion, log pipelines. | Reordering across partitions; consumer logic becomes more complex if strict order is needed. |

| Tiered storage & compaction optimization | Reduce compaction pressure on the newest data and offload older data to cheaper media. | Large LSM-based systems (RocksDB, Cassandra, Scylla, ClickHouse-like engines). | More moving parts; requires careful tuning and metrics to avoid surprises. |

5. Query Skew & Range Scans → Smarter Query Routing and Index Sharding

5.1. Problem

Even when keys are evenly distributed, queries might not be:

- “Give me last 100 events for user X” → 1 shard, very often

- “Scan orders between ID A and ID B” → specific small range

- “Search posts for

tag = hot” → only a few shards have relevant data

Hashing doesn’t help here because the skew comes from the query pattern, not key distribution.

5.2. Solution Pattern: Distributed Indexes + Smart Routing

You want the router/query layer to know:

- Which shards have relevant data

- How to spread load across replicas

- When to offload heavy aggregations to background jobs/materialized views

5.3. Techniques

| Technique | Idea | Helps with | Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharded secondary indexes | Index (e.g. by tag, status, tenant) is itself partitioned across many nodes. | Hot filters like WHERE status='OPEN' or WHERE tag='hot'. | More write amplification and index-maintenance complexity; heavier background work. |

| Scatter-gather with pruning | Route queries only to shards that can satisfy the predicate, not to all shards. | Range queries, partial scans, filtered searches. | Router must maintain metadata about shard key ranges; stale metadata can cause inefficiency. |

| Replica-aware read routing | Direct reads for hot ranges to less-loaded replicas. | Read-heavy hotspots, hot tail latency. | Increased replica counts; potential for read-after-write inconsistency depending on consistency guarantees. |

| Precomputed materialized views | Move expensive aggregation work off the hot path and into background jobs. | Heavy analytics queries over the same dimensions. | Freshness vs cost tradeoff; more streaming/ETL complexity. |

6. Physical Node Imbalance → Microshards & Automatic Rebalancing

6.1. Problem

Even with a perfect logical distribution, one machine can be overloaded:

- Noisy neighbor on shared hardware

- Hotter set of partitions “by accident”

- More compaction / GC on a subset of shards

- One bad disk or NIC

Now you have a hot shard by virtue of placement, not data distribution.

6.2. Solution Pattern: Many Small Virtual Shards (Microshards)

Instead of having, say, 64 partitions each pinned to a single node, you use thousands of tiny logical partitions (virtual nodes, vnodes, microshards) spread over the cluster.

When a few microshards become hot, the cluster can:

- Move just those microshards to underutilized nodes

- Replicate them more aggressively

- Throttle or reshard them

6.3. Techniques

| Technique | What it does | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistent hashing with many virtual nodes | Each physical node owns many small slices of the keyspace. | Smooths out randomness; makes rebalance granular. | More metadata; slightly more complex routing and state management. |

| Load-based shard movement | Move microshards away from overloaded nodes based on CPU/QPS/latency. | Targets actual hotspots instead of just “big shards”. | Shard moves can cause cache coldness; need careful throttling. |

| Autoscaling based on hot shard metrics | Scale out when certain shards show sustained hotness, then redistribute. | Lets you pay only when load spikes; good for cloud-native setups. | Requires robust per-shard metrics; scaling lag can still cause transient pain. |

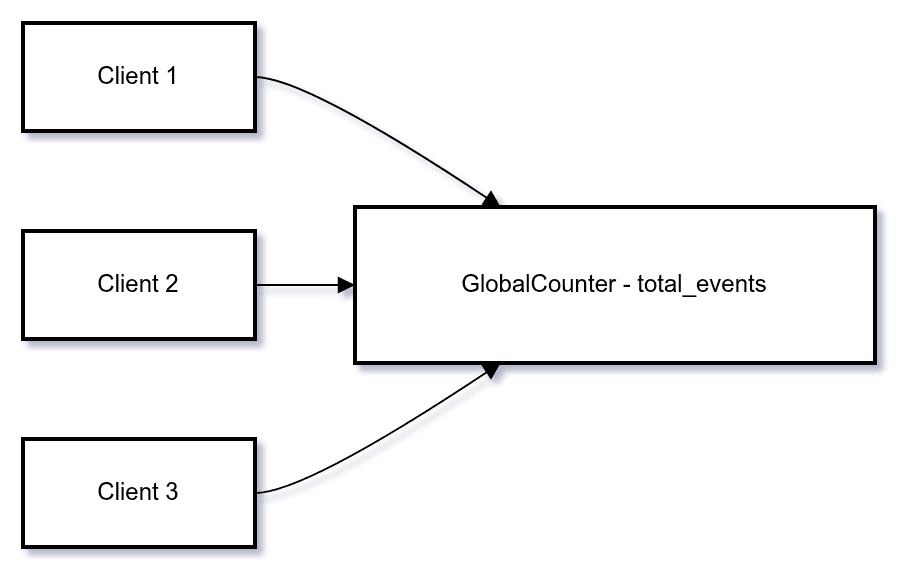

7. Global Logical Keys → Distributed State, Not Centralized State

7.1. Problem

Some things are inherently global:

- Global “current version” of a config

- Global counters (total users, total events)

- Global locks or leases

- Global rate limiter bucket

If you implement these as a single key or row, that key becomes a guaranteed hot spot.

7.2. Solution Pattern: Decompose Global State

Break global state into many smaller, less synchronized pieces:

- Sharded counters / CRDTs instead of a single counter.

- Per-scope limits instead of one global rate bucket.

- Distributed lock services instead of one database row.

7.3. Patterns & Tradeoffs

| Pattern | How it works | Where it shines | Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRDT / sharded counters | Maintain multiple partial counts and merge them (using CRDT join) to get a global value. | Metrics, analytics, dashboards, non-critical quotas. | Exact consistency can be weaker; you may see temporarily stale or approximate values. |

| Hierarchical rate limiting | Limits per region / cluster / tenant, then aggregate up. | APIs with high fan-out, multi-region systems. | Designing fair & safe hierarchies is tricky; more state to manage. |

| Dedicated lock/lease services | Use a Raft/Zookeeper/etcd-like system rather than ad-hoc DB locks. | Leader election, config rollouts, coordination. | Another distributed system to run; limited QPS; still can be a logical bottleneck if abused. |

| Scoped “global” keys | Turn one global key into many “per-scope” keys (global#us-east-1, etc.). | Multi-region configs, region-scoped variables. | Must reason about cross-scope divergence; extra complexity if you truly require global invariants. |

8. Storage-Engine Hotspots → Engine-Aware Design

8.1. Problem

Even if traffic is balanced, the underlying storage engine can make some shards more expensive to maintain:

- Compaction storms for specific SSTables/segments

- Write amplification skewed to a few partitions

- GC or memory pressure isolated to particular key ranges

8.2. Solution Pattern: Align Logical Sharding With Engine Behavior

Key ideas:

- Prefer append-friendly patterns over in-place updates.

- Use tiered storage (hot vs cold) so old data doesn’t penalize hot keys.

- Keep shard sizes bounded, so compaction jobs don’t balloon.

8.3. Techniques

| Technique | What it addresses | Strengths | Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shard-level compaction control | Heavy compactions on a small set of shards. | Lets you smooth IO usage and avoid compaction storms. | Engine-specific; requires deep tuning and good metrics. |

| Tiered or time-partitioned tables | Mixing hot and cold data in the same structures. | Keep hot data small and in fast storage; archive cold data. | More complex retention/migration logic; additional tables/indexes. |

| Bounded shard size & split policies | Very large shards that are expensive to compact. | Prevents any shard from becoming too “heavy” to move or maintain. | More shards to track; more frequent splits & metadata updates. |

9. Unified View: Root Causes vs. Solution Patterns

Here’s the “one big table” you can reference later.

| Root Cause | Typical Symptoms | Main Techniques | Key Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot keys | One tenant/user/key dominates QPS and CPU. | Key salting, sharded counters, adaptive key splitting. | Fan-out on reads, aggregation complexity, weaker ordering guarantees. |

| Temporal / time-series hotspots | Newest time window or newest IDs are much hotter. | Write sharding within time buckets, multiple “hot” partitions, compaction tuning, tiered storage. | Readers must hit multiple buckets; more complex data layout and routing. |

| Query pattern skew | Same shard(s) hit by popular queries or range scans. | Sharded secondary indexes, scatter-gather with pruning, replica-aware routing, materialized views. | More metadata and background work; potential for higher read amplification. |

| Physical node imbalance | One machine’s CPU/IO much higher than peers. | Many virtual nodes, load-based shard moves, autoscaling, smarter placement. | More metadata; careful handling of cache coldness and rebalancing costs. |

| Global logical keys | Centralized counters, locks, configs become bottlenecks. | CRDTs, sharded/global counters, hierarchical limits, dedicated lock services, scoped “globals”. | Weaker global invariants, more complex semantics, extra infrastructure. |

| Storage engine hotspots | Some shards spend outsized time compacting or GC’ing. | Shard-level compaction controls, bounded shard sizes, hot/cold separation. | More operational tuning; engine-specific concerns. |

10. Putting It All Together

If you were designing a new system today and wanted to be reasonably robust to hot shards, a good baseline would be:

-

Random hashing with many microshards

- Start with 10×–100× more logical shards than physical nodes.

- Route via consistent hashing.

-

Shard-aware router with rich telemetry

- Track QPS, latency, CPU, and storage per shard.

- Use this to drive resharding and autoscaling.

-

Hot-key detection + key-splitting

- If per-key QPS crosses a threshold, automatically salt/split.

- Expose a simple aggregation layer for reads.

-

Write sharding for time-series workloads

- Use time buckets + randomness rather than purely monotonic IDs.

- Keep bucket sizes bounded and split when needed.

-

Distributed index and query layer

- Secondary indexes are themselves distributed.

- Support scatter-gather with pruning and replica-aware routing.

-

Storage-engine-aware policies

- Avoid huge shards; cap shard size.

- Tune compaction to avoid IO storms.

-

Avoid single global keys

- Use CRDT-style counters and hierarchical limits.

- Reserve a dedicated, low-QPS system for locks and coordination.

That combination is more or less what the big players converge on, with different flavors and tradeoffs.